While there was a great deal of early native settlements with developed cultures that we can ascertain from archaeological discoveries, by the time of the first Europeans the area was sparsely settled and the area seemed to be primarily preserved as a battleground between the Iroquois, Shawnee, and Cherokee, all who utilized the area’s resources, without really attempting to settle into the area. However, some of the native Sapelo and Tutonis did join in war with the Iroquois and were rewarded by becoming a sub-branch of the Seneca, called by Americans, the Blackfoot Seneca. Others of the native tribes were incorporated by other means, and of course others simply migrated eastward. This does not mean the natives simply welcomed the settlers, there was a great deal of warfare against encroaching white men.

But, move in the white man did. Early attempts to achieve land grants east of the Blue Ridge, however, were generally frowned upon by both the homeland and the colony itself. So to understand the settlers in West Virginia we have to understand indenturetude. Farley Grubb’s great work on the subject shows us the fallacy taught in school that everyone came willingly and contracted to come to America to work off passage. In school I learned it was a seven-year contract, and I guess from what I understand that is still taught. The problem we have with this understanding is it's basically wrong. There were indentured servant contracts signed by an English magistrate and were binding upon arrival when the servants were bid upon unloading. Some of these were willing, many were forced, or pushed upon people to avoid jail. Those were generally for much longer contractual lengths of service. The demand for labor in America was greater than the supply, so people were often rounded up, especially the Irish and the Welsh, and to a lesser extent the Irish. These were sent under redemption contracts that would be negotiated upon arrival. The first blacks from Africa in the North American colonies also often negotiated for under the redemption contract, although not knowing English they often didn’t understand they were being sold via specific contracts and I imagine most never realized they were only slaves for a specified time. But that is not really as weird as it sounds. Contracts for labor began as selling others into labor for specified periods of time. Slavery did not begin as contracts, but labor contracts began as being placed into slavery for a specified time.

William Penn, however, made a concerted effort to enlist Germans to come to America. There were advertisements and offers of great benefits and Germans who could make it to the ports in America did come willingly. But they were mostly underage and single women, according to Grubb. It had long been thought it was mostly German families, but using embarkation records and sales records when they arrived at American ports, Grubb has disproved that to be the case. And when they arrived at the English ports they were not taken to a magistrate, they simply boarded and were brought here on redemption contracts to be determined upon arrival.

In the 17th century, before slavery became the dominant method (and without any redemptions available) for labor, a great portion of white indentured went into labor, it was still 25% of the indentured service even in the 18th century after slavery began to take hold. But Grubb’s records show that only 1% of the Germans went into labor. But primarily that is because single women and children were more likely to go into service. Now for those beyond the majority, servitude was at least until they reached their majority, and they were various means to extend contracts. In Pennsylvania, if a servant fell ill, and then recovered, time loss for illness could be doubled and added to the length of the contract. And so , below Pennsylvania, and where there was little English or colonial government authority, on very well worn paths that the Native Americans had developed, the German indentured would escape. When George Washington surveyed much of what is now West Virginia there were hundreds of German squatters living in the area, but without title.

It was not however until the mid-18th century that the coal mining story begins. Waterways from the west became important and tributary ports, wharfs and canals were established. Probably more because of simply better traps, the beaver supply began to be scarce and a new source of industry needed to be developed. Salt from the Kenawa region and logging timber were developed and some coal was found and sold to power the burgeoning steam, traffic for industry and shipping. Also, as white indentured labor in Virginia became frowned upon and enough black slaves were able to replace them, many of them retreated westward and settled in the mountainous valleys. Government became more officious and that meant contracting the industries and that meant replacing the independent lifestyles of the former indentured to work for those that now contracted them to work for less than was needed to survive wages. Many had not been indentured laborers but they were nor forced into labor. Companies owned not only the mines, but the towns where the miners worked, and the stores where they bought supplies and at the end of the pay period the miners had earned less than that had spent and so had nowhere to go but stay in the mining towns. It seems kind of like slavery to me. They got shelter, food & clothing in return for their labor. Theoretically they were paid, but the shelter, food & clothing was more than they were paid, so their pay was debit pay. They owed more than they earned, so even though they were paid, they had negative earnings.

After the civil war, rail lines now made it possible to transport more and more coal, miners were forced into longer hours of work and higher quotas; and it wasn’t like anyone was eager to go work in the minefields, so they were kind of stuck. Immigrants were flowing into the country and many were trying to escape the coal fields in Europe and while some were directed back to the mines, it just was not a dream job. So boys would enter the mines at a young age and live long to father a couple of more boys to replace them.

Back in the bosses’ houses who financed the mines and the railroads via the banks all was not rosey. There were continuous post civil-war panics, and so these bank and railroad and mining owners continued to have to bail out the failures of their own gluttony. The panic of 1893 was probably the worst in American history. The depression of the 30’s seemed to endure longer, but at least until the great bailout of 2008-2009, there had never been anything like 1893. The crisis started on the heels of the panic of 1890 with banks in the interior of the country. This created the instability in the economic activity prior to the panic. The recession raised rates of defaults on loans, which weakened banks’ balance sheets. Fearing for the safety of their deposits, men and women began to withdraw funds from banks. Fear spread and withdrawals accelerated, leading to widespread runs on banks. (Now please keep in mind who had money in the banks–it was not farmers whose income was seasonal and in debt to banks; and it was not laborers who were in debt to their owners and had nothing to deposit in the banks. Secondly,gold reserves maintained by the U.S. Treasury fell to about $100 million from $190 million in 1890. At the time, the United States was on the gold standard, which meant that notes issued by the Treasury could be redeemed for a fixed amount of gold. The falling gold reserves raised concerns at home and abroad that the United States might be forced to suspend the convertibility of notes, which may have prompted depositors to withdraw bank notes and convert their wealth into gold. In June, bank runs swept through midwestern and western cities such as Chicago and Los Angeles. More than one-hundred banks suspended operations. From mid-July to mid-August, the panic intensified, with 340 banks suspending operations. As these banks came under pressure, they withdrew funds that they kept on deposit in banks in New York City. Those banks soon felt strained. To satisfy withdrawal requests, money center banks began selling assets. During the fire sale, asset prices plummeted, which threatened the solvency of the entire banking system. In early August, New York banks sought to save themselves by slowing the outflow of currency to the rest of the country. The result was that in the interior local banks were unable to meet currency demand, and many failed. Commerce and industry contracted. In many places, individuals, firms, and financial institutions began to use temporary expediencies, such as scrip or clearing-house certificates, to make payments when the banking system failed to function effectively.

Industrial production fell by 15.3 percent between 1892 and 1894, and unemployment rose to between 17 and 19 percent.1 After a brief pause, the economy slumped into recession again in late 1895 and did not fully recover until mid-1897.

While the narrative of each panic revolves around unique individuals and firms, the panics had common causes and similar consequences. Panics tended to occur in the fall, when the banking system was under the greatest strain. Farmers needed currency to bring their crops to market, and the holiday season increased demands for currency and credit. Under the National Banking System, the supply of currency could not respond quickly to an increase in demand, so the price of currency rose instead, increasing interest rates lowered the value of banks’ assets, making it more difficult for them to repay depositors and pushing them toward insolvency. At these times, uncertainty about banks’ health and fear that other depositors might withdraw first sometimes triggered panics, when large numbers of depositors simultaneously ran to their banks and withdrew their deposits. A wave of panics could force banks to sell even more assets, further depressing asset prices, further weakening banks’ balance sheets, and further increasing the public’s unease about banks. This dynamic of course creates unemployment, lowers wages because of the competition to have any wage, creates violence and makes people upset with the government. Those that have a little now have less, the smaller businesses are replaced by larger more consolidated businesses and banks who reduce wages and raise prices putting workers and farmers ever more under the thumb of the industrialists.

The War Begins

As competition for jobs increase, the non-dream jobs find more seeking non-dream work, the competition for labor lowers the wages of the non-dreamers because other non-dreamers who have no jobs at all non-dreams them into accepting the non-dream jobs of those already voided from dreaming who are forced into even fewer dreams by working for even less.

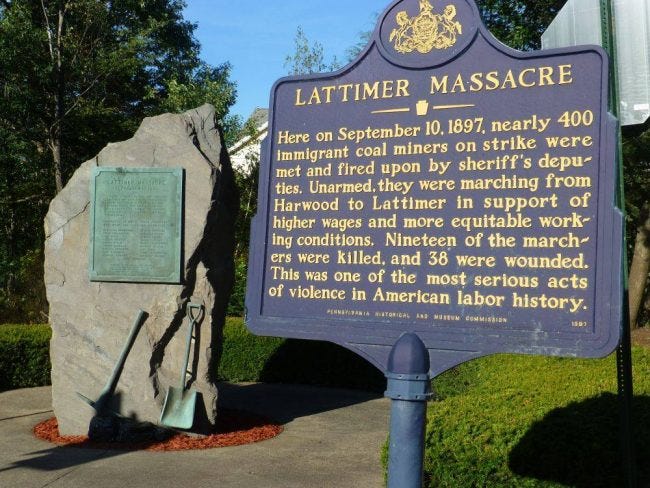

In reaction to this the mining wars actually began in the Pennsylvania mines, on Sept. 10, 1897, 19 mine workers were killed and dozens were wounded in the Lattimer Massacre. A strike had begun weeks prior as miners from eastern Pennsylvania protested extremely dangerous working conditions, unpaid overtime, and the company store and the reduction of wages. About 400 miners, mostly immigrants, began an unarmed peaceful march to Lattimer to support the newly formed United Mineworkers there. When they arrived, Luc

erne County sheriff James Martin and his deputies opened fire on the men and boys.

Source: Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission

But our West Virginia story begins in the same post ‘93 panic when the coal miners began attempting to organize the coalfields of southern West Virginia to fight the injustices of the coal mine labor system. As was common in most labor struggles of this era, mine owners and operators fiercely resisted the workers’ efforts. In 1912, the conflict came to a violent head in the Kanawha and New River coal fields with a “wildcat” strike in which workers launched a work stoppage without union assistance. This marked the beginning of what has come to be known as the West Virginia mine wars. When operators in the Paint Creek Valley in Kanawha County refused to grant union workers a modest pay raise that was on par with what other regional companies had given to their employees, thousands of nonunion miners went on strike. Soon, 7,500 nonunion miners in nearby Cabin Creek joined them, spurred by the oppressive rule of the coal operators. The strike that ensued followed the typical pattern of a work stoppage, but when company guards started forcibly evicting mining families from company-owned homes, the miners fought back. The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike of 1912 turned into a 13-month long struggle that resulted in the death of 12 strikers and 13 company men.

While the United Mine Workers (UMW), the nation’s main labor union representing American coal miners, had not initiated the strike, they were eager to make inroads in the region, so they lent their full support to the striking miners. To assist the strikers, the union sent both renowned organizer Mary Jones (“Mother” Jones) and UMW vice president Frank Hayes to the region. The coal operators responded by recruiting strikebreakers from the South and New York state and hiring 300 Baldwin-Felts mine guards to bust the strike. The Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency was a private security firm hired by coal mine operators throughout the country to violently suppress strike activity in mining areas of Appalachia and the West.

The Baldwin-Felts guards constructed iron and concrete forts outfitted with machine guns throughout the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike area. They continued to evict mining families from company housing, destroying $40,000 worth of personal property including furniture in the process. The guards enforced the coal mine operators’ control over the entire terrain of company towns, preventing strikers from using bridges across mountain streams or leaving on trains traveling through the area by beating those who attempted to board. Perhaps the most infamous example of the violence they employed was the nighttime ride of the Bull Moose Special.

The Bull Moose Special was a train car, the sides of which were reinforced with iron plating with machine guns installed inside. On the night of February 7, 1913, coal operator Quinn Martin, along with Kanawha sheriff Bonner Hill, turned off the lights and drove the train through Holly Grove, a tent colony the UMW had established for striking miners and their families, firing into the homes and tents. An Italian miner, Francis Francesco Estep, was shot in the face and killed while trying to protect his pregnant wife. Even though several miners had died during the violent strike, Estep’s murder enraged the striking miners. The news of the attack on Holly Grove made national headlines the following day, enraging one merchant to the point where he sent both guns and ammunition to the striking miners.The fighting paused when West Virginia’s governor, William E. Glasscock, declared martial law, sending the state militia into the region. While miners initially welcomed the militia, believing that they would restore peace and protect their rights, their views quickly changed when it became clear the militia was there solely to break the strike. For the first time as far as I am aware, in American history martial law was executed on the scale that it was in West Virginia from 1912 to 1913. Without warrants, the soldiers arrested 200 strikers and strike leaders (including Mother Jones), imprisoned them, and tried them before military tribunals for inciting violence just as had been done during the civil war–but to an even greater extent.

Governor Glasscock’s brutal execution of martial law of course meant it was all going to remain as it was. None of the guards and coal operators faced any consequences for their roles in the violence.

1921 AP Dispatch from Charleston, W. Wa.

The miners — whites, Blacks, and European immigrants — banded together, bent on doing something about their treatment by coal operators. They became known as the “Red Neck Army” for the distinctive bandanas around their necks.

“Those people had a specific purpose in mind,” Roberts said. “And they were willing to die for that. And because they were willing to die for that, we’ve all had a good living, a much better life than we would have had had they not gone on that march.”

At least 16 men died and many more were injured before the miners surrendered to federal troops in September 1921.

In 1920, southern West Virginia had the nation’s largest concentration of nonunion miners. Company towns were prevalent and oppressive. Miners lived in employer-built encampments and were paid in private company currency, called scrip that was only good for purchases at the company store. Scrip was a fraction of what a dollar was. Matewan Police Chief Sid Hatfield sympathized with the unionization efforts Hatfield gathered his deputies in defense of the minors to protect the from the companies’ militia. Fifteen months later, agents from the same firm fatally shot Hatfield. Infuriated, miners gathered by the thousands, intent on confronting the companies and freeing imprisoned miners accused of violating martial law in Mingo County. The miners made it to Logan County, whose sheriff, Don Chafin, was anti-union. Chafin assembled law enforcement officers, coal operator guards and recruited civilians to hold off the advancing miners, including using biplanes to drop a few homemade bombs. Federal troops sent by President Warren Harding eventually arrived by train. Thirteen miners and three deputies were killed and 47 others were wounded. Hundreds of miners later were charged with treason and murder. (Who says we don’t try people for treason in America?). This setback at Blair Mountain stalled the UMW’s efforts in southern West Virginia and caused membership to plummet. It would not be until FDR signed laws that permitted collective bargaining in the 30’s that the miners in West Virginia would even consider joining the UMW again. But then came Taft-Hartley and membership once again began to decline.

West Virginia is a breeding ground for anti-ethnic sentiment. I wonder if your school lessons tell you how you escaped from being indentured only to become the slaves you so much despise, yourself. Maybe instead of teaching you about the benefits of being white, maybe they should be teaching how your labor was enforced and how you were benefited from. Maybe they should tell you about how you attempted to revolt from your own white servitude. Then maybe you would understand you are in league with your own enslavers when you espouse your rhetoric of hatred. I do not blame your despair whatsoever, but open your eyes to who turned you into slaves in the mines because it sure wasn’t those you despise.

I really like your reporting on the Mining "Wars" They weren't wars so much as massacres of underpaid, impoverished by the mine owners (Which is how Joe Manchin made his money - coal and oil) You final paragraph is great advice and the major reasoning for banning text books and restricting education - we certainly don't want our little darlings to know how vicious these descendants of wealthy mine and plantation owners really were and certainly not how recent is heir abuse.

You're a bit off on your centuries, Ken. The first documented arrival of African slaves was early 17th Century; 1619 to be exact when 20 to 30 African slaves were brought to Virginia. By 1776 (18th Century) there were about 200,000 African slaves working in mostly southern colonies. Canals were being built in the early 19th century, 1820's. Indentured servants first arrived 12 years prior to the African slaves. Indentured workers continued to be used until outlawed in 1917. (20th century.